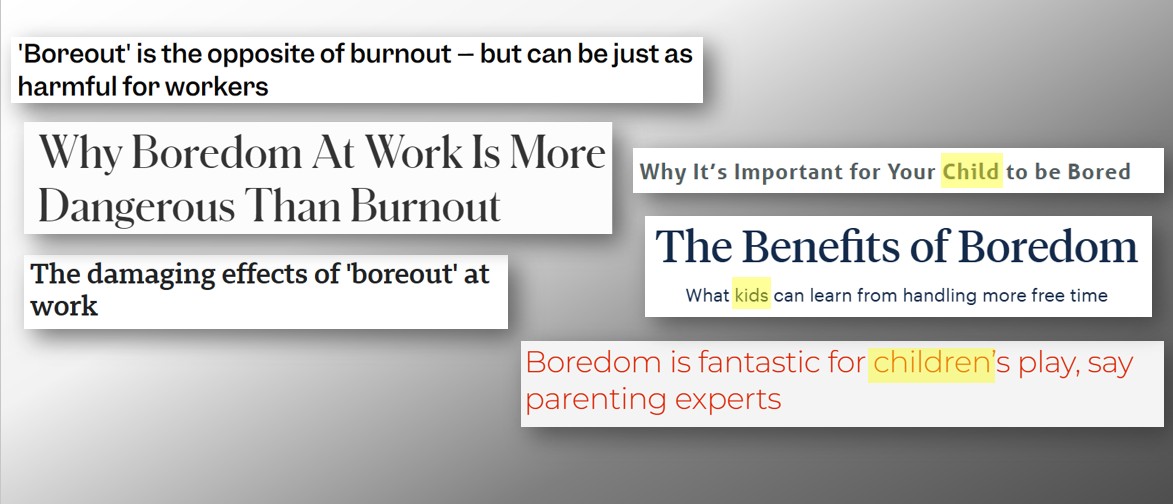

Chronic boredom is harmful to adults, causing stress, disengagement, and poor well-being. Academic researchers have shown that boredom in the workplace can be just as damaging as burnout. But search for information about childhood boredom and you’ll find the opposite message: articles describing boredom for kids as “fantastic”, “important”, and full of benefits.

News articles, social media graphics, parenting discussions, and even policy proposals are full of praise for how great boredom is for children. Why do so many adults disresgard children’s autonomy, capabilities, and intellectual needs?

Unstructured play is different than boredom

Play is a keystone of childhood. It is crucial for children to have unstructured free time in which they figure out what they want to do. Left alone, my daughter has come up with all sorts of fun ideas– building homes for her stuffed animals out of empty kleenex boxes, hand-drawing a series of mazes of varying difficulty, and inventing a murder mystery game for her matchbox cars. My daughter isn’t bored when she does these things!

However, there is a time when my daughter was quite bored, and that is when she attended school. While she made friends and never complained about going, she began to spend most of her time zoning out. She lost her previous curiosity and became quite passive. She grew accustomed to getting the right answers without trying, and began to get upset when practising piano or playing chess (activities she previously loved, but where mistakes are inevitable).

Boredom did not just impact her during the hours she was at school; it altered how she was interacting with the world. Once we returned to homeschooling, my daughter’s curiosity, creativity, and resilience quickly returned.

Boredom and Busy-ness are not opposite

Boredom is a state of weariness through lack of interest, dullness, or tedious repetition. It is not fundamentally about how much work a person has to do, but rather about how stimulating and engaging that work is. The term “boreout” refers to chronic boredom and understimulation in the workplace. Research confirms that boreout leads to poor well-being, disengagement, and stress. It increases how likely workers are to quit their jobs.

What is boredom? Sitting through a math class that is too easy (so you tune out) or too hard (so you tune out) is boring. Completing an overly repetitive task is boring. Being forced to read a book you find simplistic is boring. Many children can go days without hearing an interesting idea. Their world feels small and drab. That is boredom.

Lotta Harju, an assistant professor at EM Lyon Business School in France, who wrote her dissertation on boredom in the workplace said: “Don’t assume that keeping people busy will cure boredom. It does not.” This echoes the experience of my daughter. The problem was not that school didn’t keep her busy. In fact, she has much more free time to devote to her passions now that we have returned to homeschooling. Yet in popular culture, boredom is proposed as a counterbalance to over-scheduling.

An endless appetite for new information

An LA Times article earlier this year argued that children should not begin learning phonics until age 5 or 6. “‘I even think that it’s really wrong for parents to ever try to push reading before 5,’ said Wolf [director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners and Social Justice at UCLA]. Parents who try to teach their children to decode words at 3 or 4 may end up turning their kids off from reading instead… ‘Waiting doesn’t hurt, but there is a risk that pushing will,’ Wolf said.”

The LA Times article is not an anomaly. In education policies, parenting discussions, and popular culture, people worry a lot about children being challenged too much. There is no symmetric concern about what happens when children are challenged too little. What if children enjoy reading and find it entertaining? What are the harms when a child feels intellectually stifled or understimulated?

Throughout the article, teaching a child to read at ages 3-4 is almost entirely described in negative terms: something that is “pushed”, “forced”, or “drilled” by parents; the result of worry; the opposite of relaxing. The word “push” shows up 4 times in the article. The article promotes the misconceptions that children can’t find joy, curiosity, or satisfaction in learning a new skill and would only learn if pressured by a parent.

In a well-researched essay refuting the article, neuroscientist Erik Hoel argues that “young children have an endless appetite for new information”, one that is “too large and deep for parents to fill just by reading books aloud.” By delaying when kids learn to read, “literature is fighting for attention and relevancy [against iPads] with one hand tied behind its back for the first 8 years of life.”

While the LA Times article is about early reading, the underlying assumptions are widespread regarding children’s learning in general.

Conflating challenge, amount of free time, and foci of motivation

In discussions about boredom and challenge, a few independent variables get conflated:

- Level of challenge

- Time spent

- Internal motivation vs. external pressure

It is often assumed that something challenging must be quite time-consuming or is only a result of external pressures. Valid concerns about children being overscheduled or overpressured end up conflated with ignoring the need for intellectual engagement. Intellectual challenge doesn’t have to take much time nor be the result of external pressure!

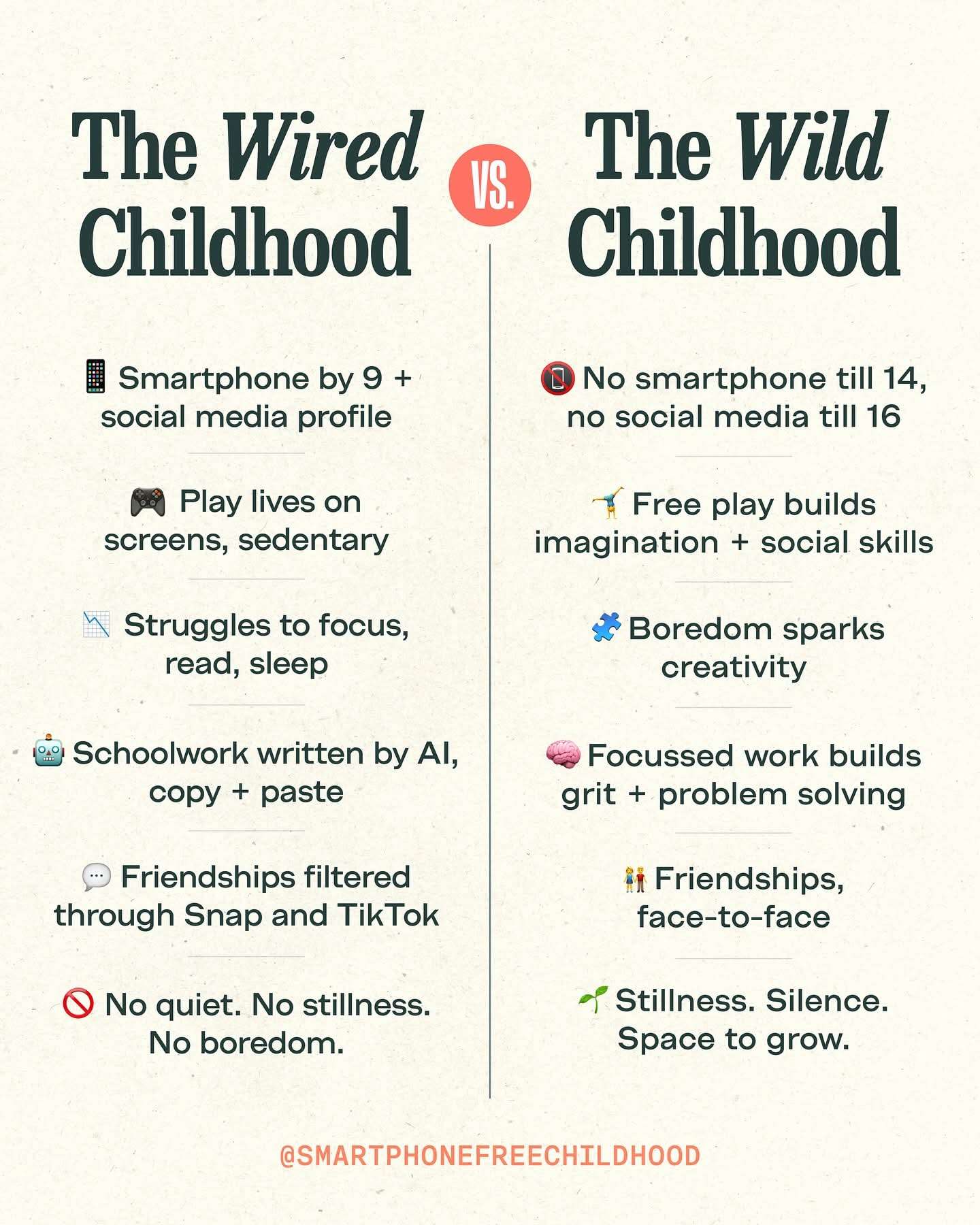

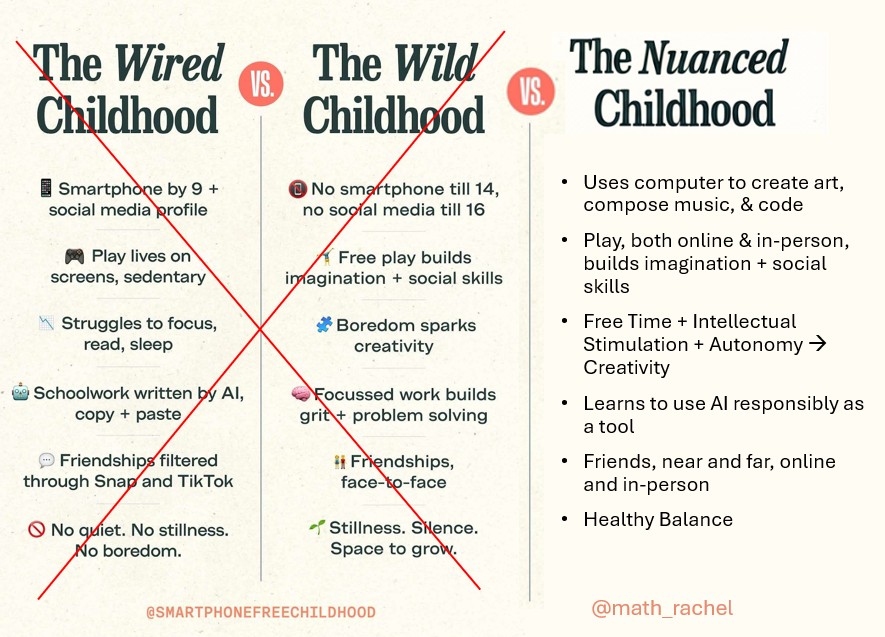

All-or-nothing thinking shows up again and again in discussions of how children spend their time. Children can either enjoy “essential moments of play, exploration and language” OR they begin learning to read before age 5, but not both (according to the above LA Times article). Children can either play on screens OR they engage in free play building imagination + social skills, but not both (as the social media graphic below suggests).

Stop relying on false binaries

Ignoring children’s need for intellectual stimulation often dovetails with movements to ban screens for children. Many children use computers to create digital art, write fiction, compose music, and code interactive games. Children can even do these activities collaboratively with their friends (I wrote more about this here).

Yet false dichotomies abound. The “wired” side of this popular graphic focuses on the worst possible version of screen use I can imagine. I don’t think children should be on social media, SnapChat, or TikTok. I don’t think people of any age should be unthinkingly copy & pasting work written by AI (although I do think AI is a helpful tool when used appropriately).

If a child had free time, read a book about outer space, and then was inspired to write about an imaginary galaxy they created, most people would consider this a positive thing. What if the child had instead watched a Professor Dave Explains Astronomy YouTube video and was then inspired to type a story about an imaginary galaxy they created? Is this now a negative use of the child’s time since it involved screens? Neither of these examples is about boredom, since the child has access to interesting stimulation (books about space or an educational videos) and useful skills to implement their ideas (hand-writing or typing).

Skills that open up the world

There are skills that open up new worlds– learning to read is a key one. Learning to code is another. Being able to write or type at a fast enough speed to get ideas out of your head and share them with others is a third (this is why I am in favor of children learning touch-typing early– I have never met an elementary-aged child who didn’t have ideas years more complex than what they could hand-write).

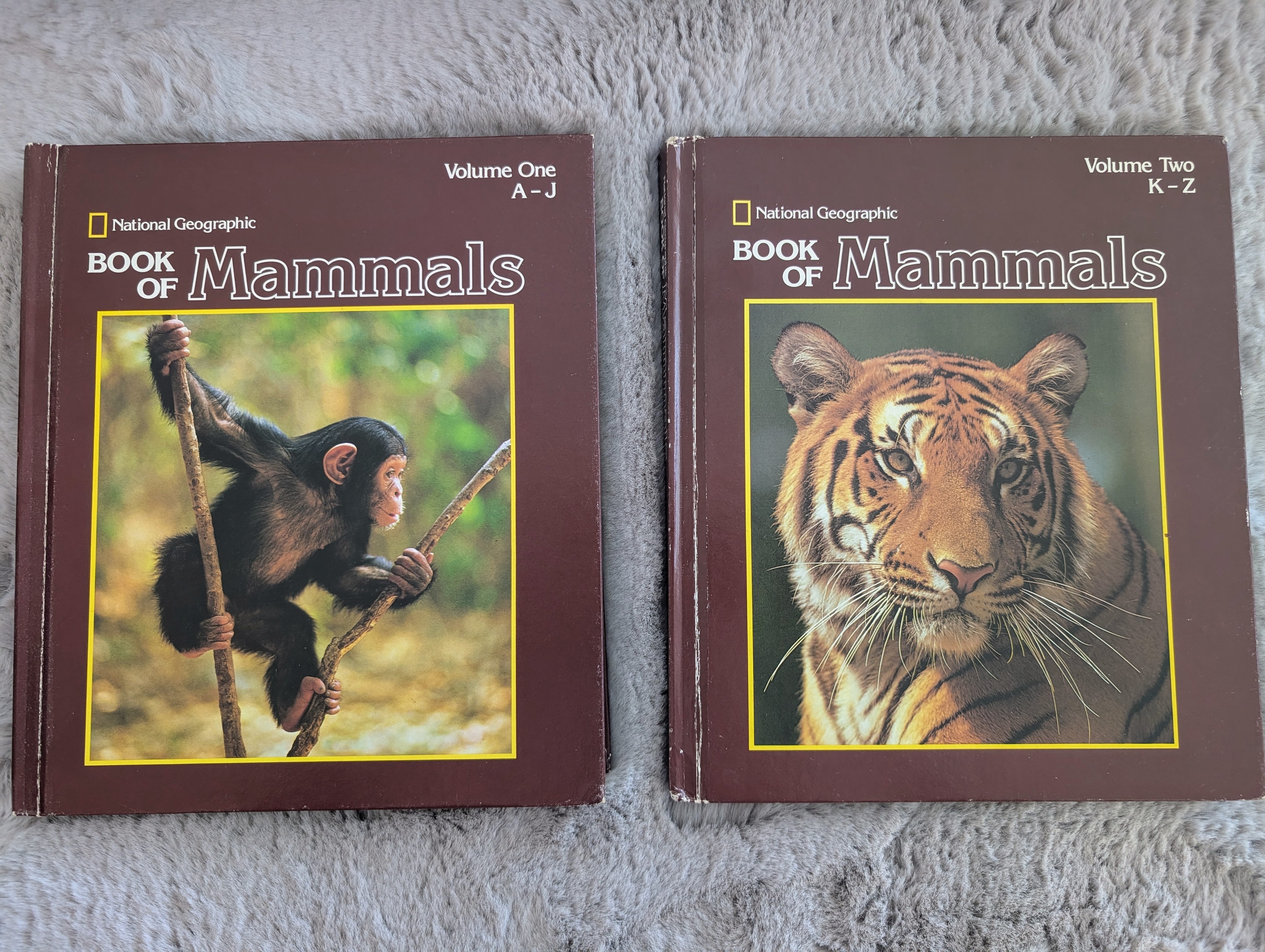

There are also objects of wonder that open up worlds. I still have my National Geographic Book of Mammals (1981 edition), a 2 volume encyclopedia full of photographs and detailed facts and maps about the world’s mammals. I remember spending hours poring over the photos and text as a child. Art supplies and engaging books (such as DK encyclopedias) can spark inspiration.

Children will not pick up a new skill or field of interest in the same way an adult could. They need guides to let them know what is out there, as well as how they can interact with the world in satisfying ways. Many children enjoy mastering skills that let them better explore the world (reading), express themselves (art, coding, writing, music), and/or are intellectually satisfying (patterns, puzzles, chess). It is important to customize your approach to your child’s needs. Try new things, and if your child seems stressed and disengaged, you can stop and wait until they are older.

Children’s Needs

It is important to be precise about what children need. Overloaded schedules and overemphasis on standardized testing are destructive and harmful trends. But forcing children to be bored is not the solution. It is important that children of all ages have enough free time, autonomy, and rest. This goal is orthogonal to if they are being given intellectual challenges and opportunities to broaden their world.

An understimulating, unfulfilling job is harmful for adults. I hope that we can see a similar awareness of how boredom impacts children. All children deserve exposure to appropriately calibrated challenges that they find interesting and engaging.

Further reading

You may also be intersted in: